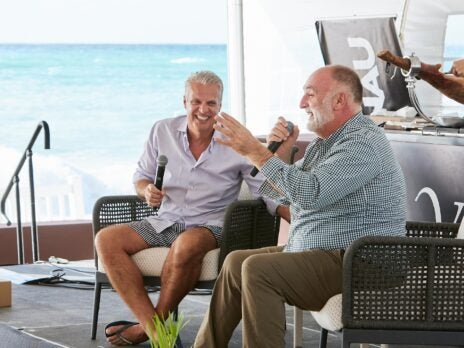

Australia’s most successful professional golfer Greg Norman, branded The Shark by golf writers almost 40 years ago, is still attacking life. Here he shares with Shaun Tolson his fondest memories from his career — they’re not what you think — as well as his perceived role in broadening golf’s global appeal.

When the Open Championship is next contested in July, 2021 at Royal St Georges Golf Club, the world’s best professional and amateur golfers will attempt to conquer the historic links course set along England’s southeastern shore just as Greg Norman did 27 years earlier. During that memorable tournament in 1993, the then-38-year-old Australian set a handful of records, including the lowest aggregate score for the championship and the lowest final round recorded by any winner — two achievements that went unmatched for decades.

“That final round was one you just dream about,” says Norman. “I cannot say in my whole career that I have played a round and not missed one shot, but that day I never mishit a shot. I hit every drive perfectly, every iron perfectly, and only made a mess of one putt. That was the best I ever played in my life.”

The victory secured Norman’s second major championship (and his second Claret Jug); it also marked the 68th of 91 total professional victories that the Hall of Fame golfer would claim throughout his storied, 33-year career. More impressive than all of those accomplishments — including the 331 weeks that Norman sat atop the World Golf Rankings — is the manner in which golf’s Great White Shark first took up the game and his meteoric rise once he did.

Norman was a natural athlete who spent much of his childhood living along the Queensland coast. There, he devoted his free time to playing rugby, Aussie rules football, cricket and — most passionately — surfing. Golf didn’t enter the picture, not until Norman was 15 years old and caddied for his mother, who was a highly capable player with a single-digit handicap. After the round, when his mother retired to the clubhouse for tea, Norman again slipped her bag over his shoulder, only this time he went out onto the course for himself. “I said, ‘If she can play the game, I gotta be able to play it,’ he recalls. “And that was it.”

Norman played four holes that afternoon, and while he cannot recall the specifics of his unsupervised introduction to the sport, he acknowledges that he walked off the course encouraged. Soon Norman was partaking in junior clinics on Saturday mornings, carrying his own bag of six cobbled-together clubs. His first official scorecard was marked with a 108, and his introductory handicap was 27 — the highest that the Australian Golf Union would issue at the time. A year and a half later, however, Norman was a scratch player. Five years after that, he was hoisting the winner’s trophy at the West Lakes Classic, the first of the big money tournaments on the Australian golf circuit that year. It was only Norman’s fourth professional event.

“Because I was a very good surfer, I knew where my body was in space at any given time,” Norman says, attempting to explain his rapid improvement as a teenager. “All the ingredients were there, so I just learned how to rotate around the golf ball.”

Eventually, lessons were instilled through private instruction, but in the beginning, Norman relied on two books written by Jack Nicklaus: Golf My Way and My 55 Ways to Lower Your Golf Score. “I studied his grip, stance, ball position, posture and takeaway. That’s all I studied,” Norman recalls. “I could relate to Jack. I didn’t know him, but [after reading those books] I felt like I knew him.” In time, he really would.

During the 1976 Australian Open — Norman’s third professional tournament — the prodigious Australian was paired with the Golden Bear for the first two rounds. Because their last names were so close alphabetically, Norman and Nicklaus’ lockers were side by side. “I got to know him, and he was very embracing,” Norman recalls. “I felt comfortable with him very quickly.”

The two Hall of Famers, then at very different stages of their respective careers, shared another connection at that time. Because of Norman’s quick rise up the ranks of Australian golf — not to mention his flowing blond hair, which bore some resemblance to Jack’s — golf writers began calling Norman the Bear Cub. “I’m glad it didn’t set in the way that it could have,” Norman says of the moniker. “It was flattering, but I didn’t want to have that kind of connection. I’ve always wanted to be independent.”

Five years later, the media branded Norman the Great White Shark, a nickname partially inspired by the golfer’s aggressive style of play at The Masters in 1981. “As a kid, I was always in perpetual motion and attacking life, so it was a perfect nickname,” he says. “It was 100% synonymous with me.”

Reflecting back on his career, Norman acknowledges that there are plenty of moments and events that transpired on the course that he remembers fondly, but those aren’t his fondest memories. “There are hundreds of shots that I can sit back and reflect on if I wanted to,” he says. “But they didn’t have the impact on my life the way that meeting people through golf did. It’s not about playing the game of golf, it’s about the people that I met. Those are the things that I cherish the most. It really broadened my horizons more than I had ever anticipated.”

Through his accomplishments on the course, Norman had an opportunity to meet world leaders such as President Nelson Mandela of South Africa, President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, Prime Minister Bob Hawke of Australia, and US Presidents George HW Bush and Bill Clinton, among other dignitaries. In many cases, those introductions led to long-term relationships, which have since helped Norman in some of his philanthropic endeavors. When a tsunami ravaged Indonesia in 2004, for example, Norman brought Presidents Bush and Clinton together to raise millions of dollars in a single day. “Being philanthropic in the most philanthropic country in the world is not hard to do,” Norman says, not wanting to make a big deal of the charitable work that he’s done while living in the US. “But paying it forward is important.”

Norman also learned from those world leaders and business moguls how to conduct himself professionally. Prime Minister Hawke, for example, taught Norman the art of effective public speaking, and those lessons helped him to later leverage the Shark nickname into a portfolio of successful international business enterprises — some connected to golf and others independent of the sport. In particular, Norman learned the value of quiet observation. “It gave me the confidence to say the right thing at the right time,” he says of the moments he spent with numerous presidents, prime ministers and entrepreneurs. “The power of listening is way greater than the power of talking.

“When you start asking a lot of questions, you can see these other opportunities that can come into your favor,” he continues. “Once you see them you still have to build a business plan. It’s not easy and it doesn’t happen overnight. It took 15 to 18 years for me to build credibility and to establish a footprint of what I wanted to do, but I haven’t veered off course since.”

Despite Norman’s various golf-related enterprises, it is his course-design business that the 65-year-old deems to be the most significant. Through courses that he’s built in far-flung areas of the world such as Vietnam, Norman has introduced the merits of capitalism in otherwise socialist or communist countries. His course-design projects have strengthened golf’s popularity in India, Argentina and Mexico, and in some cases — like with Ayla Oasis in Jordan — his courses have even opened the door for the sport to flourish in new regions around the world.

Although he would enjoy taking on a mentor’s role for some of the younger players on the PGA Tour, much the way Nicklaus acted as a mentor to him during the first half of his own playing career, Norman admits that those opportunities haven’t yet presented themselves. “I have a wealth of experience and information,” he says, acknowledging that right now his work as a course designer provides the best medium through which he can share it. “That might be more my outlet. That’s how I can grow the game around the world.”

Photos: ©Michael O’Bryon