When Yannick Alléno arrived in London to set up his very first restaurant in the UK, his phone was ringing off the hook. Clare Smyth, Jason Atherton, and Claude Bosi were among the culinary talents calling to welcome him to the city.

“All these chefs rang to say they were really happy to have me in town and to offer me help with finding suppliers,” he beams. “It felt like a moment of great solidarity between us.”

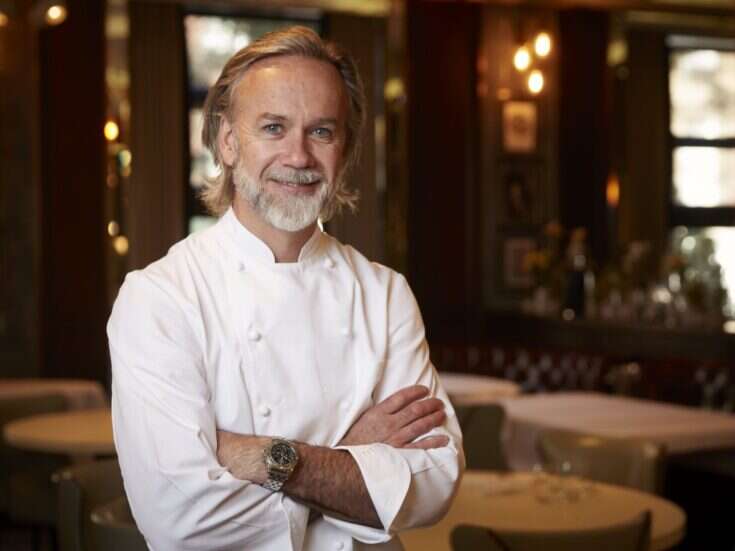

We’re sitting in the dining room at his glamorous new restaurant – Pavyllon at Four Seasons Park Lane. Behind us, chefs in tall white hats drift through the open kitchen preparing for the lunchtime service.

[See also: Mauro Colagreco on his Hotly Anticipated London Debut at Raffles]

I can’t resist asking whether he felt a little competitive; the chefs he mentions have, after all, been bestowed with some seriously impressive accolades (Smyth’s three-star restaurant is widely regarded as one of the best in London).

“No no no!” he laughs, without skipping a beat. “We have plenty of stars already. It’s enough!”

Indeed, the revered French chef has amassed a total of 15 Michelin stars across his burgeoning collection of restaurants including three at Alléno Paris, two at L’Abysse, and one at the original Pavyllon in Paris. These days, he tells me with a conspiratorial smile, stars are no longer the goal: “I just want to make my guests happy”.

Catching my raised eyebrow (I’m not entirely convinced he isn’t hoping to dazzle inspectors), he continues: “Honestly [the stars] are not my concern… what keeps me awake at night is if I hear one of my diners has been disappointed. Being a chef comes with a lot of responsibility.”

And, while he has carved out an enviable reputation as one of the planet’s superstar chefs, his London debut remains a daunting one. “The quality of the restaurants and the energy is crazy,” he says, pausing for a moment as if he still can’t quite believe he is really here.

“I’ve wanted to come to London for a very long time… but Londoners aren’t waiting around for another French chef. Now, it’s time for us to make it happen and be the absolute best we can.”

Food has always been everything to Alléno. He grew up behind the counter in bistros run by his parents in the suburbs of Paris. Summers were spent learning to cook with his grandmother at her house in the countryside and in a restaurant in a little village where his cousin, Jean-Marc, worked as a chef (“I was the mascot of the team!”)

At just 15, he left school and got his first proper job in a professional kitchen, working under Gabriel Biscay at Le Royal Monceau in Paris. It wasn’t easy – but Alléno’s dedication to his craft never wavered.

“I was talking to my mum about this recently,” he recalls, “She said, ‘You don’t remember this, but when you used to come back home you would have blood on your feet from working so many hours.’ I never complained though… I loved it.”

Alléno continued to leapfrog between some of the world’s fiercest kitchens, working closely with Roland Durand and Martial Enguehard at Sofitel Porte de Sèvres. But it was at Drouant – an iconic brasserie in the heart of Paris – that he really honed his skills under the tutelage of chef Louis Grondard.

It wasn’t long before he secured his first head chef position at Scribe, scooping two Michelin stars within three years of taking over the kitchen. In 2003, Alléno became head chef at Le Meurice winning the coveted three-star accolade in just four years.

Having firmly cemented his reputation, he opened his first eponymous restaurant, Alléno Paris, at the Pavillon Ledoyen to overwhelmingly positive reviews; seven months after opening he had been awarded three Michelin stars once again.

What makes his food so special? The secret, he tells me, is in the sauce. His obsession with this element of cuisine began over a decade ago with a terrine. “You know terrine, the pâté?” he says. “I had cooked a venison and there was a spoonful of jelly left that would usually go in the trash. When you taste it it’s like ‘Wow – crazy’… I called my lab and said ‘I want that!’”

And so, Alléno enlisted Dr. Bruno Goussault (widely recognized as the founder of sous vide cooking) and embarked on a quest to make the perfect sauce. Over 500 tastings later, they finally cracked it and, in 2013, patented the extraction technique.

How does it work? The unique method involves cooking an ingredient sous vide (vacuum sealed in a precisely regulated water bath) at a specific temperature for several hours to create an intensely flavored liquid which is then extracted to concentrate the sauce even further.

Not only does this pack a real punch when it comes to taste (I was lucky enough to dine at Pavyllon and try Alléno’s famed sauces for myself) but this unique cooking method results in significantly lighter, healthier dishes, as the intense natural flavor from the extraction process means chefs no longer need to add the generous dollops of butter and cream favored in traditional French cooking.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Alléno went back to the lab incorporating fermentation techniques to further intensify the flavour and blending different extractions together to create ever more complex sauces. Ultimately, he credits 80% of the success of each plate of food he serves in his restaurants as resting solely with the sauce.

“If you lose sauces,” he stresses, fixing me with his impenetrable stare, “you lose your own language. You have to understand that the sauce is the verb of French cuisine.”

Next, he plans to use his revolutionary extraction technique to craft guilt-free chocolates eschewing dairy, butter, and sugar while somehow, he promises me, still delivering on flavor. His biggest fear, he admits, is the restaurants he visits across the globe where “everything tastes the same… the same Wagyu beef… the same fatty, salty things. It has a real cost on your health.”

For now, though, his attention is firmly on his new venture. As the lunchtime service approaches, the kitchen is getting louder, the chefs moving with a greater sense of urgency – there’s a buzz and excitement in the air that only comes with a newly opened restaurant.

“I have one of the best teams in the world,” Alléno tells me, catching my glance. He looks around the dining room, taking it all in as he gets up to leave. “For me, there’s nothing better than this… it’s what I love to do.”

It’s this passion and inventiveness that sets him apart from even the planet’s top chefs. And, while he insists he isn’t thinking about stars, I can’t help but feel it won’t be long until London’s Michelin inspectors come knocking.

[See also: Marcus Wareing on Critics, Feuds, and his Fortuitous TV Career]