Occasionally when Marcus Wareing watches back an episode of MasterChef: The Professionals, a contestant will completely disregard his critique of their cooking. Of course, they never say this to the Michelin-starred chef’s face. Any objection – however tiny – is reserved for the film crew when Wareing is safely out of earshot.

“It’s only happened once or twice,” he tells me with a grin, “but each time I’ll think, fucking hell – why didn’t I know about that? Probably because they knew it would piss me off.”

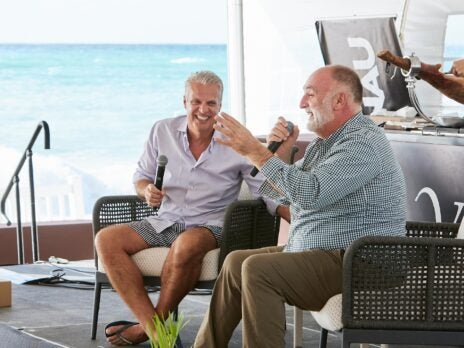

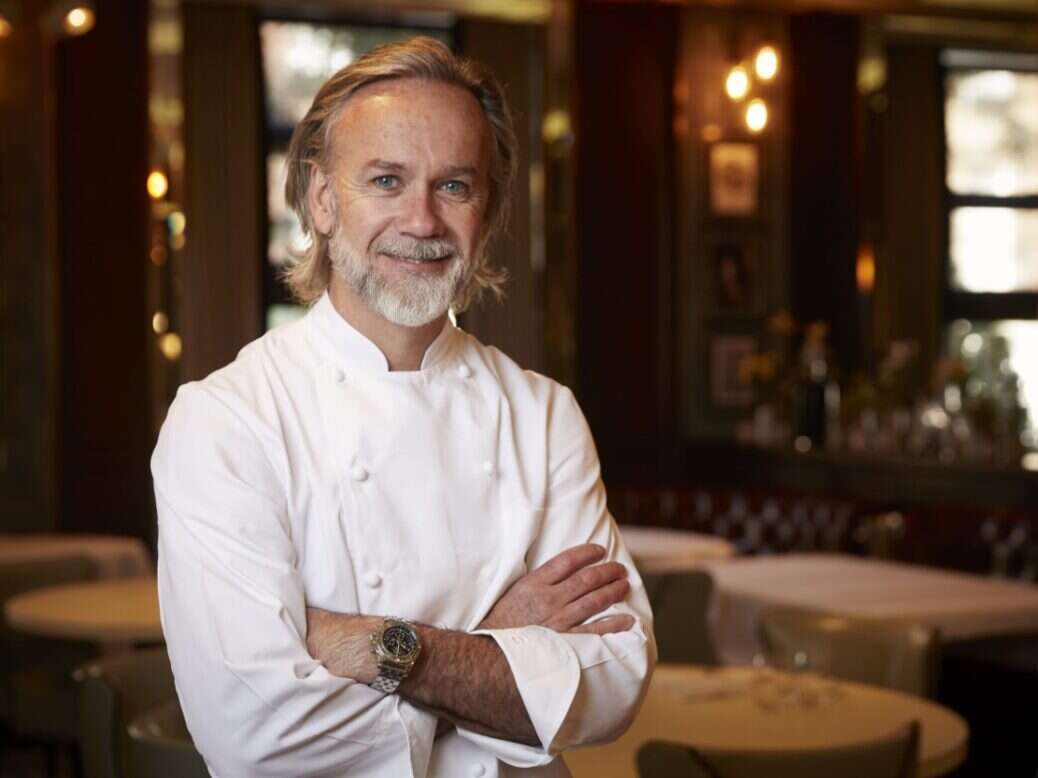

We’re sitting in the wood-paneled dining room in his eponymous restaurant at The Berkeley – one of London’s swankiest hotels. Moments earlier I was ushered in through the heavy oak doors to find Wareing sipping coffee in his crisp chef’s whites.

Under his steely gaze, I felt, for a brief, unnerving moment how contestants must feel when they enter the MasterChef kitchen for the first time. Then I remember with a jolt of relief that I’m here for an interview – there will be no fish filleting or chicken deboning this morning.

[See also: Monica Galetti on her Return to Masterchef]

It’s little wonder professional chefs flounder under his stare. Wareing has high standards and rarely holds back when contestants on the British cooking show fail to live up to his expectations. But that’s exactly what makes him so compelling to watch; after almost four decades of toil in some of the planet’s fiercest kitchens, Wareing has paid his dues.

He gets his relentless work ethic from his father, who worked as a fruit and vegetable merchant in Southport, Merseyside. In the evenings after school, Wareing would pack potatoes and help his dad with deliveries.

“My father would bring home a load of rotten fruit and my mum would stew it down and make a ton of apple pies and put them in the freezer,” he recalls. “There was always cookery at home – mostly meat and two veg.”

At 15, Wareing got his first job in a professional kitchen at the hotel restaurant where his older brother was already working as a chef. The following year, while studying catering at Southport College, he caught the attention of one of the judges at a cooking competition.

“He asked whether I would be interested in going to work at The Savoy, which was basically like going to heaven,” Wareing tells me with a smile. But leaving everything behind proved more difficult than he could have imagined.

“I can picture the day my mum and dad left me in London,” he says. “I can remember my first bedroom and where I used to press my whites. I don’t go on the tube very often but that noise… the smell… it brings back really bad memories; scary memories.”

Whenever there was an opportunity to go home, his dad would be waiting to pick him up at the station late on Friday night for a weekend back in Southport with his family. Sunday evenings were filled with dread; Wareing will never forget the long, silent car journeys as his dad drove him back to Liverpool Lime Street.

I ask why they never spoke in the car. “I think it was because we’d said it all,” he says, pausing as he weighs up the question. “I was so nervous. There was nothing he could say to comfort me; he found it hard as well. But I would get back on the train, put my Walkman in my ears, and just get on with it. It’s no different to being in the army.”

At The Savoy, Wareing was first into the kitchen in the morning and last to leave at night. He never wavered; when he called home his dad made it clear returning to Southport wasn’t an option. “I won’t use the words he used to say,” says Wareing, “but he’d tell me, ‘There’s nothing here. This is a seaside town mate. Crack on – keep going.’”

After his stint at The Savoy, he leapfrogged between some of the country’s top restaurants working under Albert Roux at the Michelin-starred Le Gavroche and Steven Morey at Gravetye Manor in Sussex where he met his wife, Jane.

When I ask which chef has made the biggest impact on his career, though, he doesn’t skip a beat. “That’s Gordon Ramsay all day long,” he says, fixing me with his impenetrable stare. The two chefs had a highly publicized spat when Wareing was working at Ramsay’s London restaurant, Aubergine.

At the time things got nasty; the pair’s close friendship – Ramsay was best man at Wareing’s wedding and is godfather to his eldest son – descended into a bitter feud and lengthy legal tussle over Pétrus (now Marcus at The Berkeley).

Ramsay ended up retaining the name and opening a new Pétrus around the corner, while his former protégé took control of the venue (he’s still here at The Berkeley 15 years later, Michelin star in tow).

Now, Wareing seems to have mellowed and looks back at the rift as a necessity enabling him to step out of Ramsay’s shadow and move forward with his career. “All of the problems and falling out were crucial to who we are…” he trails off and corrects himself.

“Who I am. It’s not changed him but certainly that split changed my world forever. We were going down different roads. All I did was protect everything I was doing: the food I put on the plate. Am I happy? Absolutely. Have we achieved what we wanted? No, we’ve achieved more actually.”

He still has fond memories of the time they spent working together in the 90s. “It was like being part of the biggest rock’n’roll band on the planet,” he tells me.

“You’ve got the Beatles and you’ve got the Rolling Stones. Different groups clashing with each other fighting to become the top dogs. We were like that: Gordon and I were taking over some of the biggest five-star deluxe hotels in London… which I’m still sitting in today.”

And if he bumped into Ramsay this afternoon? “We’d shake hands and say hello,” he says, though he looks a little wary. “Bygones are bygones. Life’s too short. There’s so much more we’ve all got to do.”

Wareing is like this throughout our interview; breezy and laid-back one minute, defensive and irritable the next. He has little patience for chefs who place too much emphasis on the Michelin inspectors. “Does my fucking head in,” he bristles. “’I’m going for my Michelin star – I’m going for this, I’m going for that’. It’s not the Olympics. You’re not going to the World Cup. I hear it all the time – it’s the stupidest thing a chef could say.”

He is keen to stress that cooking has never been about awards or recognition; his goal was simply to set up a business like his dad. In fact, he says, winning his first Michelin star at Pétrus when he was just 25 came as a complete surprise (“I was like ‘Where the hell did that come from?”)

TV work was never part of the plan, either. The BBC came knocking back in 2014 and he took over from Michel Roux Jr. as a judge on MasterChef: The Professionals. This brought with it an added level of scrutiny; the public could be critical of his harsh feedback to contestants.

Did this bother him? “I couldn’t care less,” he says, a beat too quickly for me to fully believe him. “I never read a food column and think ‘Wow I value your opinion’ because everyone has an opinion now. What makes a columnist an expert? If you stay focused on your own goal, you’ll be fine. It’s when you start looking too far out that you’re going to get lost.”

Throughout his entire nine-year stint on the show, Wareing has employed just one MasterChef contestant: Craig Johnston who won back in 2017 and now heads up the kitchen at Marcus at The Berkeley.

To say Wareing is busy is an understatement. Tomorrow he will film the final episode of the latest series of MasterChef, next week he is traveling to Provence to begin filming his new show Tales from a Kitchen Garden. He’s also in the throes of writing his tenth cookbook.

I ask if he minds leaving the restaurant, but with Johnston at the helm, he never worries about the food. “Have I got time to peel carrots?” he says, finishing his coffee and shuffling his papers on the table. “I’ve been in kitchens for 36 years; I’ve got nothing to prove.”

His real passion, besides food, is encouraging the next generation of chefs. He’s currently working with a UK charity – Speakers for Schools – to encourage children up and down the country to consider a career in hospitality.

“When people look at me they say ‘You’re special, you’re privileged,” he tells me. “That’s the lovely thing about where I came from; I’ve got a whole new story to tell that is the opposite of what you think I am.”

[See also: Clare Smyth on Making her Mark in the World of Fine Dining]