Recent studies show that food systems account for around a third of all the world’s greenhouse gases. Let’s just digest that. Of course, restaurants — and fine dining restaurants at that — are just a small piece of that puzzle.

However, the power the world’s leading chefs hold to influence change should not be underestimated; there is a growing appetite for a more considered cuisine among both diners and the industry.

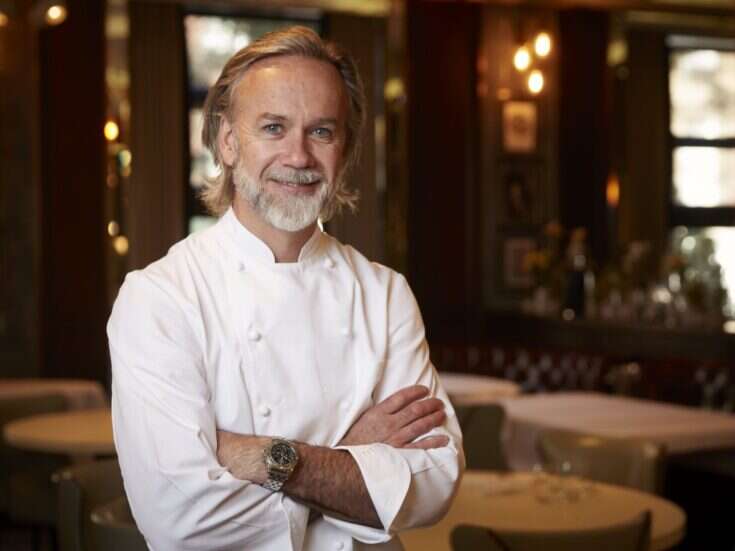

A prime example of this is the introduction of the Michelin Guide’s Green Star in 2020 to highlight restaurants at the forefront of sustainable practices. One of the world’s best chefs also happens to be leading the way when it comes to sustainability: Eneko Atxa. We speak to him about his unwavering dedication to green gastronomy.

It was in 2012, long before the term ‘sustainability’ even entered mainstream culinary vernacular, that Eneko Atxa did something pioneering. The Basque chef, who had opened his now three-Michelin-star restaurant Azurmendi in 2005, unveiled the first glimpses of the future of green fine dining: a new glass-sculpted, bioclimatic building to house his flagship eatery, alongside a sustainability center.

Located on a flourishing hillside in the town of Larrabetzu, not far from Bilbao, the new incarnation of Azurmendi grabbed the attention of the culinary world, showcasing what might be possible when a chef makes the planet a priority. A string of eco-awards and accolades followed. But for modest Atxa, whose creative brand of haute cuisine is rooted in Basque traditions, this was never his goal.

“I understood that my most important source of inspiration, the environment that surrounds me, was running out; it was dying,” the chef explains. “And that we were late. [I was] aware that it is our responsibility to give back to the new generations what our ancestors left us to care for and preserve.

“We feel a deep respect and admiration for our environment. One has to adapt, and if you want to live with your environment, you have to start by respecting it, by taking care of it, by pampering it. [Azurmendi’s] cuisine is inspired by our seasons, our products, our tradition — and of course the potentiality of flavors.”

The restaurant was built largely from recycled materials. When diners enter Azurmendi, they are stepping into much more than a restaurant. Part culinary-research hub, part horticultural center, it remains cutting-edge despite nearing its first decade, and still makes you feel like you are being welcomed into Atxa’s home.

A whistle-stop tour around the Gold-LEED-certified structure reveals a beautiful glass-paneled dining room, reducing the need for artificial light while framing the rolling Biscay countryside. A strategically positioned greenhouse stands to the south. Here, a healthy portion of the restaurant’s fresh ingredients are grown (pre-dinner snacks are enjoyed here while you learn about the delights you’re sampling).

There is also a green roof and an abundant kitchen garden boasting herbs, edible flowers and an array of vegetables (the rest of Atxa’s fresh ingredients are sourced locally in firm support of the circular economy).

“It’s the small things that add up,” says Atxa. “We have photovoltaic panels and a seed bank with 400 varieties that were about to disappear, and we recycle rainwater. The waste of organic material that is produced goes to a composting center, and we have started a project to reuse discarded bread. We are committed to health, solidarity and sustainability.”

There is no better demonstration of this than the chef’s JakiN project, which combines his passions for people, planet and food.

“JakiN [Jaki in the Basque language means food, and Jakin means knowledge] is a center that seeks to be a front-runner using gastronomy as a social tool. In JakiN, gastronomy is linked to sustainable development, health, solidarity, anthropology, fine arts, social commitment and family-friendly working conditions, among a number of new angles we want to tackle in order to lead chefs to new values.”

Despite these efforts and his status as one of the world’s most sustainable chefs, Atxa still feels he has a long way to go.

“We are very open to receiving proposals, to people coming to tell us what we can contribute, because it is an urgent need. It is not a trend, it is an obligation. We want to do more. We are not ‘the sustainable ones’; we are just people who are trying but we are missing a lot.

“We are going to face an absolutely brutal overpopulation, where resources are less and less. Above all, I like to convey to the team that we are all part of something that has to change. Sometimes we don’t do things because we say, ‘What I do is not going to change the planet,’ but the world of food has a very high incidence of greenhouse gases — much more than all of the world’s transport. In other words, our model of feeding ourselves has a direct and negative impact on the planet.”

Talk with Atxa turns to solutions.

He says: “We have to set a small example at home; buy better [and] try not to throw practically anything in the garbage. Very basic aspects are very important because they can help us, as a society, to change things. It is complicated because, depending on the geographical situation, the population and the gastronomic trends of each country, you have to look for a different strategy. But without a doubt, there is a common denominator — that is the producers.

“There is a fundamental aspect that we are working on, which is teaching girls and boys about what products are, about how to plan an efficient purchase, how to cook food and how to preserve it to give it a longer life, and what they should do with the organic waste that is discarded. If we manage to do this, we will be creating a generation of young people empowered through the knowledge of food to cook a better future.”

This article appears in the 06 Jun 2022 issue of the New Statesman, Summer 2022