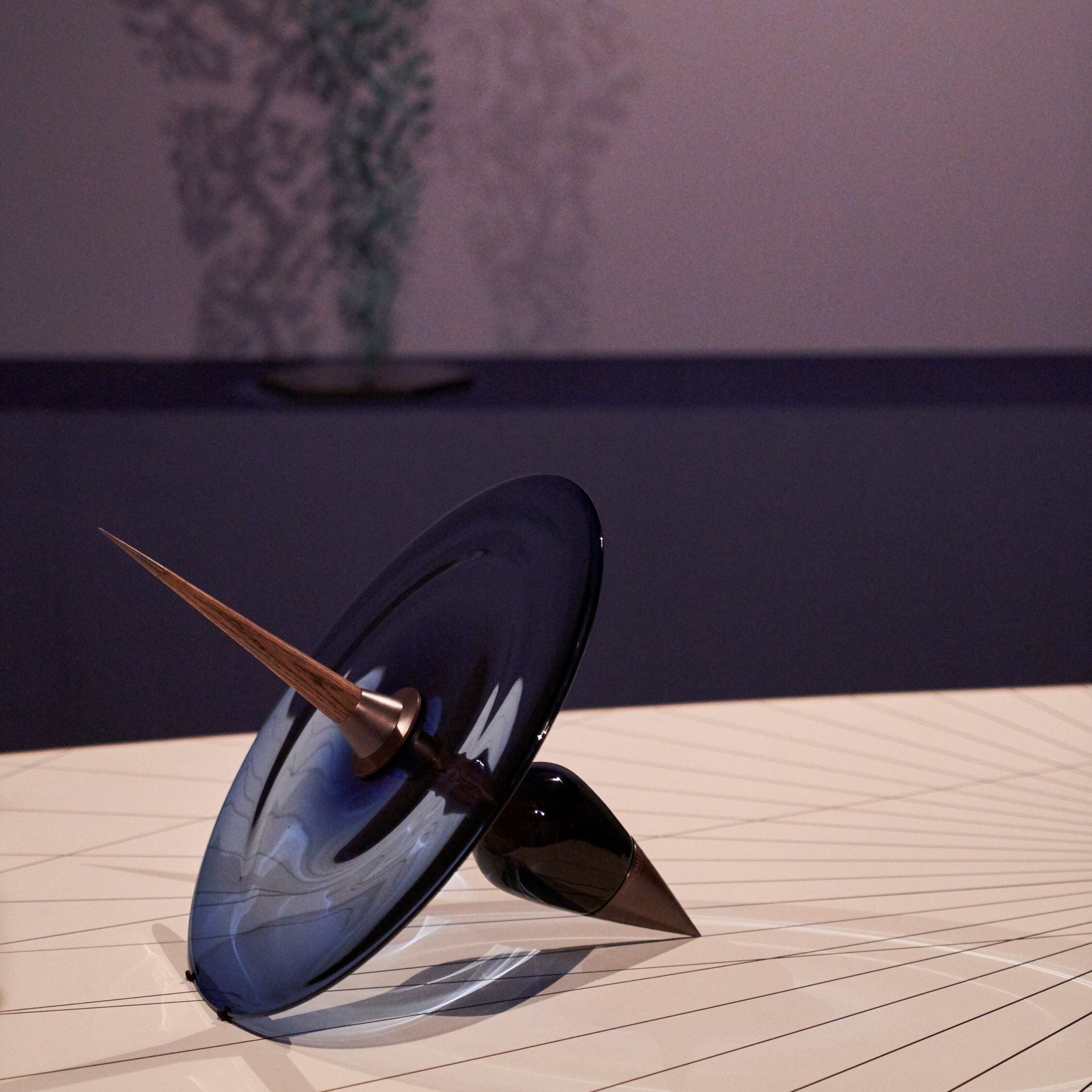

Space and time, luxury whisky, immersive art; not necessarily themes usually associated with the London Frieze, but at the annual Royal Salute Scotch Whisky bar, acclaimed artist Conrad Shawcross unveiled his new work The Limit of Everything, in which all avenues united for a mesmerizing, if not considerably unorthodox, art experience.

“They were really very supportive of me hijacking the lounge and turning it into a scary, scary bar,” Conrad Shawcross laughs. “Which I was really happy about.”

The British artist – who was once the youngest living member of the Royal Academy of Arts (“I’m not anymore,” he is hasty to clarify) – is revered for his fusion of scientific ideas and philosophies across his art, and his art pieces made in collaboration with Royal Salute is no different.

[See also: Kate MccGwire on Her Royal Salute Collaboration]

“It evolved into something quite different than I suppose they were expecting… [They] supported me turning it into much more than just a bottle,” Shawcross continues, referencing the Royal Salute bottle.

“There’s this massive experiment, the soundscape, the shadows, the table and the chairs, everything was like – we were able to spend a lot of time developing everything.”

The Limit of Everything, which was exhibited at the Royal Salute Gallery Bar alongside his epic sculpture of similar themes Time Chamber, is a dynamic light installation in which three robotic arms spin above the audience, who are sat around a table. The room is cast in shadows and light dictated by the moving piece above, and the audience further immersed with a concoction of sounds around them.

“I have a similar piece, a smaller version of that, above my kitchen table in my house,” Shawcross explains. “I’ve had many a dinner party where I have the interplay of shadows and lights and things. And actually, what’s interesting is this was much more bold in terms of the way that the table was very sparsely inhabited… And the soundscape, obviously, really brings out the potency of this sort of movement.”

“But I’ve often had parties where people don’t even notice the shadows until you point them out,” he says. “So it’s kind of like, almost your brain doesn’t consciously recognize them, even though they’re part of that. One is aware of them, or one is subliminally aware of them… So it’s kind of, to play with that.”

Shawcross acknowledges the shadows as ‘intoxicating’ and ‘quite hypnotic’, words that were bounced around by his audience coming out of the gallery bar just last week.

[See also: David Remfry on Curating the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition]

“It was great to finally show that and explore that,” Shawcross says. “And use it in a really artistic way.”

And it was especially notable that this immersive art experience Shawcross created was exhibited at the Frieze London, which celebrated 20 years last week. The contemporary art fair, held in Regent’s Park, seemed especially big this year; a joyous coming together of London’s students mingling with London’s high society, American art buyers and European celebrities, all under one roof with the city’s greatest art galleries.

“It’s hugely important in the London calendar for artists,” Shawcross explained. “I somehow by hook or crook manage to be part of the Frieze every year in some capacity. I’ve managed to have a presence in from the first fair, so that’s been amazing.” Humble words from an artist positioned at the utmost echelon of the British contemporary art scene, with sculptures and statues displayed across the world, his work exhibited from Singapore to New Zealand.

But the Frieze, Shawcross expands, “needs to up its game”. “There’s a sort of threat to the Fair,” he says. “There’s a real need for it to do more things.” The future of art, especially within Britain, is something Shawcross takes very seriously; later, when we discuss the next generation of the country’s artists, his tone hardens as government policy and priorities come up.

Yet in regard to the Frieze, “the only way it’s going to remain a dominant force in Europe is for it to be more ambitious. So I think things like this that I did, I really actually hark back to an immersive experience like Mike Nelson did, an immersive experience. Less commercial, but more experiential, things that really need to be supported within the firm to give it that credibility and that kind of gravitas.”

He does acknowledge, of course, that the Royal Salute association – Shawcross is the second artist of the brand’s Art of Wonder annual collaborations – renders the two pieces created for it as having a “commercial element”, but that “the whole imagining of this space is really just a tract driven by an enthusiastic, artistic desire to create a fully immersive experience, memorable, hopefully extraordinary.”

[See also: Follow in Barbara Hepworth’s Footsteps on 45 Park Lane’s Art Trail]

Art, to Shawcross, is something that he has “always responded to” with science and scientific ideas. Having studied at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art alongside the University of Oxford, he acknowledges that at the latter he was “surrounded with other subjects and disciplines.”

His sculptures are described by the Royal Academy as “imbued with an appearance of scientific rationality”; in the artist’s own words, entwining the two notions is at the core of what he does.

“I’ve just done a residency at Nottingham University studying the early universe and black holes,” Shawcross, who was from 2009 to 2011 the artist in residence at London’s Science Museum, tells me. He has “a couple of commissions next year about black hole mergers and gravitational waves, the process of scientific discovery generally.”

“So that’s really exciting,” he says.

I ask Shawcross of the process behind uniting art with science. How do you start with this scientific notion as stimulation, and create art from it?

He is thoughtful in his answer, taking a moment to mull over a question that I admit to him must sound pretty elementary. “It’s difficult to describe,” he says. “I guess it’s from spending hours a day thinking about ideas and trying to transmogrify those into something that’s effective, transferring an idea. It’s poetic; there’s a sort of slippage.”

Shawcross pauses before continuing. “It’s got to be able to mean different things to different people, depending on who they are and what their background is in education. All of their individual kind of perception. So it’s about losing control of meaning as well… Yeah, I mean, it’s difficult for me to say how I do it.”

He smiles across Zoom. “It’s just from training from spending years thinking about things and trying to find your unique way of flipping things around.”

As we walked out of The Limit of Everything last week, the person beside me commented that she didn’t quite know how to explain the experience, but she was very keen to do it again. Let the art speak for itself, as they say.

[See also: Tom Dixon Discusses Lights, Life, and His Latest Collection]