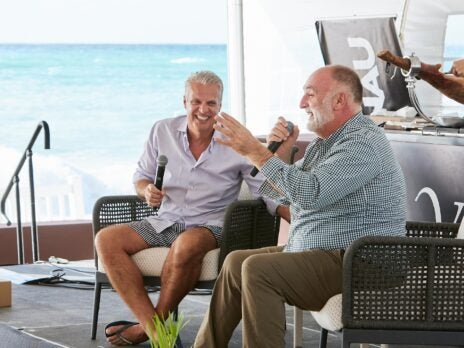

“I expected that I would not be asked,” David Remfry tells me. We’re discussing his appointment as co-ordinator of this year’s Royal Academy of Arts’ Summer Exhibition in London, the largest and oldest exhibition of contemporary art throughout the world.

“When I was asked to do this, I was flabbergasted… But the call came, and the president, Rebecca [Salter], said ‘We would love to do this – but take a few days to think about it.’ And I said ‘Rebecca, I don’t need a few days, I’ll do it.’”

I laugh. We’re only a few minutes into the interview, and David Remfry has such a gentleness in his tone, such passion for his craft – albeit in the British manner of never explicitly stating so – that talking to one of the country’s most successful and acclaimed living artists about his role in Britain’s most notable and historic event within the arts sphere feels akin to catching up with an old family friend.

[See also: Luxury and Power: The British Museum’s Dazzling New Exhibition]

Despite the ever-changing zeitgeist of our digital age and the constant evolution of the arts, the RA’s Summer Exhibition, which has been running continuously since 1769, remains as weighted today as it’s ever been.

A lengthy and exclusive admissions process, tens of thousands of artists submit their work every year in the hopes of being granted one of the biggest privileges in the international art scene: to be hung up in the RA’s Burlington House, in London’s Piccadilly. This is where household names are exhibited beside teenagers; John Constable and J. M. W. Turner’s artistic rivalry reached new heights; Banksy, famously, once got rejected.

The theme this year, selected by Remfry, is Only Connect, a phrase extracted from E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End.

“Within hours, I knew precisely what I was going to call it,” Remfry says. “Forster is an absolutely brilliant writer, and that particular one resonates. The heroine of it is German-Jewish, isn’t she, and it just brings us to current times, current prejudices, current worries.”

I tell him I love Howard’s End, the Edwardian novel that explores class, culture, and status in turn-of-the-century London through the characters of the bohemian and intellectual Margaret and Helen Schlegel sisters; the wealthy and prejudiced Wilcoxes; and the poor, downtrodden Basts.

The phrase itself is from one of Forster’s most beloved lines, written for Margaret Schlegel’s efforts to shed culture and light into the cynical and disinterested Henry Wilcox. “Only connect the prose and the passion,” Forster wrote, “and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its highest.”

[See also: The Met Opens Captivating Exhibition: Van Gogh’s Cypresses]

But what does Only Connect mean today, some 110 years on from the first publication of Howard’s End?

“We’re fully connected technologically, but we’ve never been less connected spiritually,” Remfry explains. “There’s some paradox going on, and I wanted the exhibition to be one that encompassed and embraced people, as diverse and as embracing as possible.

“I wanted the exhibition not to ignore the mess but celebrate the good side of us. “I want people to feel good when they come in. We’ve had everything thrown at us the past few years…” He pauses, and there’s a thoughtfulness to his evident weigh-up of what to say next. “War across the world…”

But Remfry doesn’t dwell upon recent events. He says: “The first thing I wanted to do is get something for the entrance. I wanted the entrance – have you been to the Summer Exhibition yet? – Maybe I should finish some sentences.”

We laugh again.

“I wanted that feeling of going into a theater, you know, with the lighting that goes on inside of it. Supposed to lift the mood of the viewer. I contacted Richard Malone, a young fashion designer. He’s made a huge fabric sculpture for inside.”

Musing and contemplative, Remfry worries he’s “jumping the gun”, and I am reminded that this is an interview, for it feels more like a delightful conversation that I could engage in for hours. I tell him I was naturally going to ask what pieces visitors should keep an eye out for.

[See also: Follow in Barbara Hepworth’s Footsteps on 45 Park Lane’s Art Trail]

“When you go into the courtyard,” he replies, “first of all, you see the statue of Sir Joshua Reynolds, up there on his tall pedestal –”

“ – immortalized with his hands poised in the air,” I interrupt.

“Yes, exactly,” he chuckles, at the iconic statue of the Royal Academy founder. “I wanted to have a woman sculpture, who stood up to him and more, but it’s very hard to find somebody whose work was available.

“I tracked down a piece of work by Huma Bhabha, but all her work is sold, so this is from a collection in Connecticut. It’s called A Ghost of Human Kindness, which I thought was rather a beautiful reference.”

Pakistani-American sculptor Bhabha is known for her reassembled, distorted presentations of the human form, a world away from the Georgian posed statue of Reynolds.

He speaks of a painting by Barbara Walker in Gallery 3, enthused to explain the artist and yet worried he is patronizing. Of course, he is not. The conversation moves to diversity, as he discusses Sir Frank Bowling, the second non-white artist ever elected to the Royal Academy.

“Shame,” he says without prompt. Remfry has been a Member of the Royal Academy since 2006. “Shame on us.”

[See also: The V&A Announces Expansive David Bowie Exhibition]

But Remfry is undoubtedly proud of the Summer Exhibition, both in its current iteration and of centuries of the show gone by. “It’s never meant to be a traditional exhibition,” he says. “By cheek and jowl… It has internationally famous names on the wall, but it also has somebody nobody knows from where I’m from – Hull – and the rest of England, Scotland, Wales. Across the world. You name it.

“An increasing number of people are exhibiting and coming to it, which is incredibly gratifying.”

Art is, I point out, especially in the Western sphere, notorious for being elitist and exclusive, traditionally restricted to the wealthy and the upper classes.

“Monochromatic,” he says. Yes, I reply, exactly that. “We haven’t reached it yet, but we’re reaching it. Recently I reread a book I got just after I left art school in 1963, British Art by Herbert Read, and he enumerates 64 British artists of the period. A whole four of those are women. He then goes on to say he hasn’t selected anyone from the Commonwealth countries. I thought, ‘This is what we’re doing. It’s appalling!”

Not even making visual art, I say, but having a relationship with it, too. “Yes. We’re excluding people. I’m very anxious we break down that barrier.”

Is there ground to be optimistic? “I’m old,” Remfry replied. He’s 80. “But I’m not giving up. I want it to change in my lifetime, so anybody – gender, race, whatever – is welcome.”

[See also: Killerton House Opens Recycled Fashion Exhibition]

I’m keen to discuss David Remfry as an artist. Having studied at Hull College of Art from 1959 to 1964, the watercolorist has exhibited regularly across the world, has collaborated with fashion designer Stella McCartney – and been the subject of a subsequent Victoria & Albert Museum exhibition – and has, when living in the Hotel Chelsea of New York City, even drawn celebrities such as Ethan Hawke and Susan Sarandon with their dogs.

Perhaps best known for his feminine etchings of bodies in movement, especially dancing people in intimate moments, his recent paintings in this year’s Summer Exhibition, Indoor Cosmology (2023), include no people, no dogs, just hanging chandeliers.

There are no humans in this painting, I say. Well, a human made it, he responds.

“I’m restless,” he says. “I don’t want to go on doing the same things over and over again.” Although he admits there is “a cyclical nature to these things”.

“But because, in a way,” he says, “religion has gone out of the window for most people, there’s a searching for some other… I’m not going to call it religion, but something. I’ve actually had five years of reading novels only by women and gone back to reading things that I sort of dismissed when I was a teenager.”

He uses Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex as an example. “I just dismissed it when I was 16, and I reread it again, and it was spellbinding! And I annotated it completely. I’ve done that with a lot of things. I’m reteaching myself.” Remfry also cites physicist Carlo Rovelli; “I think anybody would enjoy it.”

[See also: The Must-Visit Exhibitions Openings of 2023]

“It’s research,” he says. “To know what we are. Who I am.”

Indoor Cosmology, Remfry says, was birthed in Soho House New York, where he was inspired by the green glass chandeliers. “We use everything that’s around us. We’re magpies, you know, we steal from here, there, and everywhere.”

In 2007, David Remfry was given an Honorary Doctorate of Arts by the University of Lincoln, and he was asked to give a speech to the graduating students. He tells me what he said, prefixed by a humbleness embedded in his character, this time saying he didn’t think the students wanted to hear from an “old man”.

“Whatever you do,” he relays, “if you’re a writer, write every day; if you’re in the computer sciences, practice that every day. If you’re an artist, draw every day. And the second thing is to practice kindness. I’ve found that the practice of kindness is so rewarding.”

And, to return to E. M. Forster once more, human love will be seen at its highest. Remfry laughs again. “That’s all to it,” he concludes.

The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition is open from 13 June to 20 August 2023. royalacademy.org.uk