Hurricane Irma devastated the island in 2017, but when the community banded together and became more resilient, it gave the island a chance to improve and reinvent itself. The result? As Emma Reynolds discovers, an even more magical St Barths.

I’m having a very late lunch at Shellona — Hôtel Barrière Le Carl Gustaf’s beachside restaurant on Shell Beach — on Christmas Eve, and it’s positively buzzing. The festive holiday period, St Barths’ signature season, is officially underway, and the island has the crowds to prove it. Guests, who undoubtedly made reservations months in advance, are seated wall to wall; ice buckets with bottles of rosé and white wine are at every table; and the delightful aroma of the restaurant’s Mediterranean dishes, carried by tanned waiters wearing white, wafts through the elegant indoor-outdoor restaurant.

Shell Beach is the place to be for sunset. The fiery orange sun sets slowly behind the rocky cliffs, casting a striking glow on the beach. Several superyachts are anchored right offshore, and the sound of the lapping waves is eclipsed by upbeat house music inside the restaurant. Birkin-toting women air-kiss old friends, while men in crisp, white shirts puff on cigars and clink glasses. This can only mean one thing: St Barths is officially back.

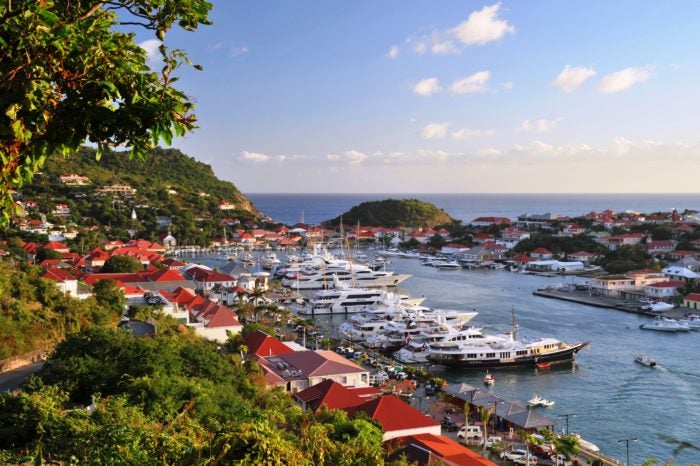

To imply that people abandoned St Barths would be silly. After all, it’s one of the crown jewels of the Caribbean islands, and a playground for the rich and famous. It is brimming with designer boutiques; dozens of paradisiacal beaches; crystal-clear, swimmable water; and a French way of life that gives it that certain je ne sais quoi. The nine-square-mile island has a verdant landscape with red-roofed homes dotting the hillsides, and there are undulating mountains, craggy coastlines, precipitous cliffs, natural pools and abundant tropical flora and fauna. It’s been called the St Moritz of the Caribbean for its natural beauty and ritzy scene.

I have vacationed on the island for the festive season for nearly two decades and seen firsthand its exceptional growth from the best-kept secret in the Caribbean to the ultimate winter escape for the world’s elite, and a required stop on the party circuit. Though it’s always been an exclusive destination, it has changed over the years: Surf boutiques have been replaced by the likes of Prada, Hermès and Bulgari, and world-renowned clubs have taken over local beach bars. The island has indeed tailored itself to its affluent guests, yet it somehow maintains a laid-back charm where locals (mostly French expats) and visitors both enjoy the finer things St Barths offers.

St Barths is two things at once: A lush, island paradise filled with natural wonder and fascinating locals, and a splashy scene where you can dine next to Leonardo DiCaprio and Roman Abramovich. You can relax with your family at a private villa, or pop magnums of champagne at one of the island’s many beach clubs — and if you want, maybe a bit of both.

After Category 5 Hurricane Irma devastated the island in September 2017, St Barths suffered a wave of destruction it hadn’t felt since Hurricane Luis in 1995. Hotels, including Eden Rock and Le Guanahani, were hit hard and closed; locals’ homes were destroyed; and the harbor was flooded. Thankfully, no lives were lost in the hurricane, and the community rallied, committed to restoring the island and coming back stronger than ever, and it also took a hard look at what the island could improve without compromising its soul.

In 2017, even the most dedicated visitors took the season off, allowing the island to get back on its feet. By 2018, St Barths die-hards (myself included) were eager to get back and help revive the island, renting villas instead of booking hotels, as many were still under construction. With Eden Rock’s grand return and a newfound excitement for the island’s future, the 2019 festive season marked the official return of the island — St Barths-aholics were happy their island was restored, and newcomers were eager to discover the hype.

After the hurricane passed, the government and many international investors who own land on the island were quick to rebuild, some even bringing in their own construction crews to repair the devastation as quickly as possible. Bruno Magras, president of the island since 2007, attributes the speedy rebuild to the locals’ can-do mentality.

“The population feels very concerned when we are hit like that,” Magras said to me inside his official office in Gustavia’s government building, where four superyachts loomed just 30 ft from his large windows. “As long as the local government provides support, everyone works hard to get back on track. That’s an important way of living. We aren’t waiting on anyone to come and help; we know we must help ourselves.”

From a tourism perspective, St Barths’ long-standing visitors were extremely concerned by the damage sustained at Eden Rock, one of the Caribbean’s most iconic hotels, and the hotel that made St Barths what it is today. It all began in the 1940s when Dutch aviator Rémy de Haenen was the first person to land a plane on the island. After falling in love with the island’s untouched beauty, he built a home atop a rock promontory situated between two pristine beaches and founded an intimate hotel. He invited his famous friends, like Howard Hughes, Greta Garbo, John D Rockefeller and the Rothschild family, to share in the island’s remote magic.

Unsurprisingly, the island became known as an elite, jet-setting destination, in part due to the immense amount of travel required to get there. To this day, St Barths’ operates one of the shortest and most challenging runways in the world, accommodating smaller planes, like the Pilatus PC-12. The small airport was even officially renamed to Rémy de Haenen in his honor.

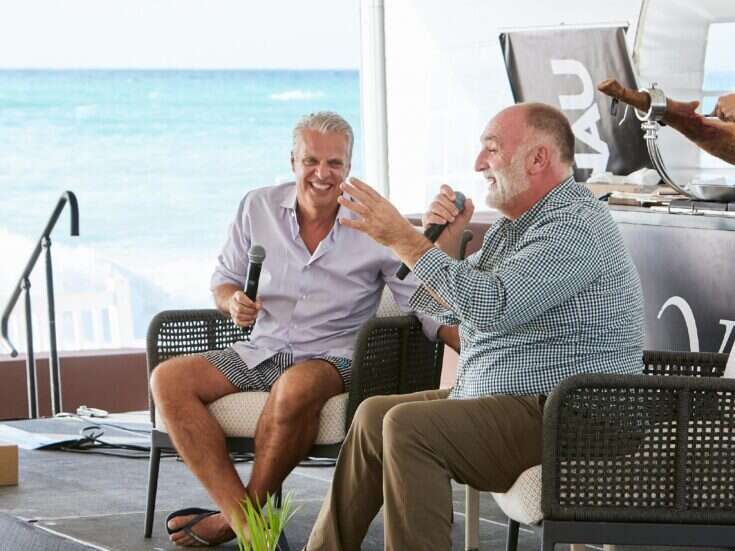

“St Barths is what it is now because of Rémy,” says Fabrice Moizan, the exuberant Eden Rock St Barths’ general manager, over lunch at the hotel’s Jean-Georges Vongerichten-helmed Sand Bar. “[Because of Rémy] Eden Rock is the core of St Barths.”

The hurricane allowed Eden Rock to reflect on its past and thoughtfully consider what it wanted to bring into the future. Before this, the hotel’s popularity never allowed it to fully close. In this new era, paying homage to the man that started it all felt right. The lobby bar is aptly named Rémy Bar, which Moizan calls the core of the hotel. It has a British-colonial aesthetic and an impressive cocktail menu (order the Eden Colada, a delicious mix of two rums, fruit juice and champagne — this is St Barths, after all). You can even live like Rémy once did in the De Haenen suite, an ultra-chic, modern replica of his original house on the top of the rock. It’s hidden from the rest of the resort, and has stunning vistas of the sea from a private wraparound terrace.

The hotel also redesigned the interiors of its suites and villas, and added a new fitness center and spa; the Beach Bar; a boutique and library; and three sensational new suites atop the rock, in place of its former dinner restaurant, bringing the hotel’s total room count from 34 to 37. “This is what we envision for the next 15 to 20 years,” says Moizan. “We want to keep a vibe that is welcoming and easygoing. We retain the chicness and elegance without being too pretentious. It’s a good balance.”

During the repair and renovation, preventing damage from another hurricane was top of mind. The Sand Bar’s deck, which sits right on the beach, was raised by three feet; and actual submarine doors (painted in Eden Rock’s signature red, of course) access the hotel’s kitchen, fitness room and electrical room, but can also be sealed shut to protect each room from water damage. Guest feedback has been amazing, according to Moizan. When the hotel announced in May 2019 that it was reopening in November, it was fully booked for festive season in less than two weeks.

Eden Rock might be celebrating its return, but not every hotel is up and running yet. This spring, the brand-new Hôtel Barrière Le Carl Gustaf (formerly an independently owned boutique hotel) will open its doors. Its bar, Shellona, has been open since November 2018, giving guests a glimpse into the luxurious transformation of the property. On the other, quieter side of the island, Le Guanahani will open in October. It’s one of the island’s oldest hotels, and it is situated on a private peninsula with residential-style rooms and suites.

Hotels and restaurants are adding finishing touches, including LVMH-owned Cheval Blanc St-Barth, which recently debuted a new wing of suites. Many new restaurants have also recently opened, including Victoria and Fish Corner in Gustavia and Al Mare at Le Sereno, helmed by Raffaele Lenzi, who runs the restaurant at the hotel’s sister property in Lake Como, Italy. Whether you’re in downtown Gustavia or enjoying St Jean (a charming town that’s home to Eden Rock, plenty of beach clubs and idyllic beaches), the entire island feels fresh and new.

With the island’s incredible resurgence, concerns about over-development have plagued locals. After speaking with Magras, these fears seem unfounded. “Sixty-five percent of the island will not be buildable,” Magras says. “Too much development will kill what we have. It’s difficult to maintain the success we have without going too far, but the final goal is to keep what justifies the success of the island: social stability, cleanliness, safety, great hotels and great French gastronomy.”

With increased tourism, the president is mapping out a plan to improve all aspects of St Barths. This includes putting unsightly electrical lines underground; securing the roads (anyone who has driven on the island knows its terrifying turns and too-close-for-comfort cliffside encounters); installing fiber optics to improve internet speed; and adding 120 parking spaces in Gustavia. It’s impossible to visit St Barths without renting a car, but the current parking situation can’t meet the demands of the myriad Mini Coopers and Mokes.

“St Barths is unique, from Trinidad to Jamaica. It’s a way of development that you don’t find elsewhere. For other islands, it’s too late to replicate. What we did can’t be transposed, not even in Europe. We did it at the right time,” Magras says.

Magras is concerned about protecting the natural beauty of the island. He doesn’t want to cut too many new roads, expand villa properties or introduce too many new hotels on the island, for now. Over the years he has been approached by, and subsequently denied, larger-scale hotel developments. He has also denied requests to lengthen the runway to allow private jets to land, and increase the number of berths in the harbor. “The natural beauty could change, and I don’t want to do that. We have to live with nature, too,” Magras says.

After the hurricane, locals emphasize how the storm has banded the community together, ultimately reconnecting them with and reigniting their love for the island. “What happened in September 2017 is very difficult to describe,” says Luc Lanza, general manager of Le Toiny St Barth and a resident of the island for 25 years. “The island has become stronger and ‘brand new.’ In this situation, you can really see how locals and tourists are linked with the same spirit as St Barths lovers.”

By January 2, the island begins to quiet down before the next wave of vacationers. Traffic stops, parking is easy to come by and many yachts have sailed out of the harbor. It’s my last night after two weeks on the island, and I am having dinner at Santa Fé, a perennial favorite French- Creole restaurant, and one of the oldest restaurants on the island (of more than 50 years). The menu has remained virtually unchanged for decades — it even still has the same tank holding freshly caught lobster to make perfectly grilled langouste. Reflecting on the island’s return, I’m reminded that the new and the old can live in perfect harmony.

St Barths isn’t going anywhere; in fact, one might say this comeback has given the island a whole new lease on life.

Images: Tourisme de Saint Barthelemy, Oetker Collection’s Eden Rock-St Barths, Fabrice Rambert, E Labouerie, Michael Gramm